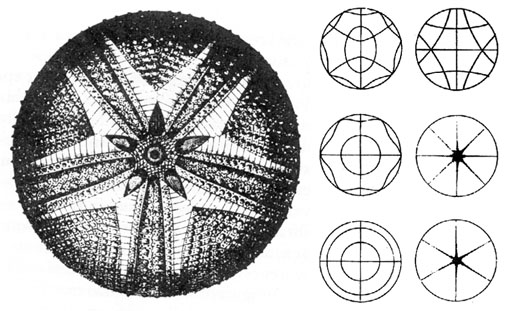

>> Vibration patterns on Chladni Plates

Metal plates covered with fine sand,

resonated at modal points and producing geometric patterns.

This is seen compared with a sea-urchin.

--| The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality

--| and the Physical Constitution of Man

http://www.elib.com/Steiner/Lectures/BridgeBet/

When man is studied by modern scientific thinking, one part only of the

being is taken into consideration. No account whatever is taken of the fact

that in addition to his physical body, man also has higher members. But we

will leave this aside today and think about something that is more or less

recognized in science and has also made its way into the general

consciousness.

In studying the human being, only those elements which can be pictured as

solid, or solid-fluidic, are regarded as belonging to his organism. It is,

of course, acknowledged that the fluid and the aeriform elements pass into

and out of the human being, but these are not in themselves considered to be

integral members of the human organism. The warmth within man which is

greater than that of his environment is regarded as a state or condition of

his organism, but not as an actual member of his constitution. We shall

presently see what I mean by saying this. I have already drawn attention to

the fact that when we study the rising and falling of the cerebral fluid

through the spinal canal, we can observe a regular up-and-down oscillatory

movement caused by inhalation and exhalation; when we breathe in, the

cerebral fluid is driven upwards and strikes, as it were, against the

brain-structure; when we breathe out, the fluid sinks again. These processes

in the purely liquid components of the human organism are not considered to

be part and parcel of the organism itself. The general idea is that man, as

a physical structure, consists of the more or less solid, or at most

solid-fluid, substances found in him.

--| The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality

--| and the Physical Constitution of Man

http://www.elib.com/Steiner/Lectures/BridgeBet/

When man is studied by modern scientific thinking, one part only of the

being is taken into consideration. No account whatever is taken of the fact

that in addition to his physical body, man also has higher members. But we

will leave this aside today and think about something that is more or less

recognized in science and has also made its way into the general

consciousness.

In studying the human being, only those elements which can be pictured as

solid, or solid-fluidic, are regarded as belonging to his organism. It is,

of course, acknowledged that the fluid and the aeriform elements pass into

and out of the human being, but these are not in themselves considered to be

integral members of the human organism. The warmth within man which is

greater than that of his environment is regarded as a state or condition of

his organism, but not as an actual member of his constitution. We shall

presently see what I mean by saying this. I have already drawn attention to

the fact that when we study the rising and falling of the cerebral fluid

through the spinal canal, we can observe a regular up-and-down oscillatory

movement caused by inhalation and exhalation; when we breathe in, the

cerebral fluid is driven upwards and strikes, as it were, against the

brain-structure; when we breathe out, the fluid sinks again. These processes

in the purely liquid components of the human organism are not considered to

be part and parcel of the organism itself. The general idea is that man, as

a physical structure, consists of the more or less solid, or at most

solid-fluid, substances found in him.

Man is pictured as a structure built up from these more or less solid

substances (see Diagram I). The other elements, the fluid element, as I have

shown by the example of the cerebral fluid, and the aeriform element, are

not regarded by anatomy and physiology as belonging to the human organism as

such. It is said: Yes, the human being draws in the air which follows

certain paths in his body and also has certain definite functions. This air

is breathed out again. - Then people speak of the warmth condition of the

body, but in reality they regard the solid element as the only organizing

factor and do not realize that in addition to this solid structure they

should also see the whole man as a column of fluid (Diagram II, blue), as

being permeated with air (red) and as a being in whom there is a definite

degree of warmth (yellow). More exact study shows that just as the solid or

solid-fluid constituents are to be considered as an integral part or member

of the organism, so the actual fluidity should not be thought of as so much

uniform fluid, but as being differentiated and organized - though the

process here is a more fluctuating one - and having its own particular

significance.

Man is pictured as a structure built up from these more or less solid

substances (see Diagram I). The other elements, the fluid element, as I have

shown by the example of the cerebral fluid, and the aeriform element, are

not regarded by anatomy and physiology as belonging to the human organism as

such. It is said: Yes, the human being draws in the air which follows

certain paths in his body and also has certain definite functions. This air

is breathed out again. - Then people speak of the warmth condition of the

body, but in reality they regard the solid element as the only organizing

factor and do not realize that in addition to this solid structure they

should also see the whole man as a column of fluid (Diagram II, blue), as

being permeated with air (red) and as a being in whom there is a definite

degree of warmth (yellow). More exact study shows that just as the solid or

solid-fluid constituents are to be considered as an integral part or member

of the organism, so the actual fluidity should not be thought of as so much

uniform fluid, but as being differentiated and organized - though the

process here is a more fluctuating one - and having its own particular

significance.

In addition to the solid man, therefore, we must bear in mind the 'fluid

man' and also the 'aeriform man.' For the air that is within us, in regard

to its organization and its differentiations, is an organism in the same

sense as the solid organism, only it is gaseous, aeriform, and in motion.

And finally, the warmth in us is not a uniform warmth extending over the

whole human being, but is also delicately organized. As soon, however, as we

begin to speak of the fluid organism which fills the same space that is

occupied by the solid organism, we realize immediately that we cannot speak

of this fluid organism in earthly man without speaking of the etheric body

which permeates this fluid organism and fills it with forces. The physical

organism exists for itself, as it were; it is the physical body; in so far

as we consider it in its entirety, we regard it, to begin with, as a solid

organism. This is the physical body.

We then come to consider the fluid organism, which cannot, of course, be

investigated in the same way as the solid organism, by dissection, but which

must be conceived as an inwardly mobile, fluidic organism. It cannot be

studied unless we think of it as permeated by the etheric body. Thirdly,

there is the aeriform organism which again cannot be studied unless we think

of it as permeated with forces by the astral body. Fourthly, there is the

warmth-organism with all its inner differentiation. It is permeated by the

forces of the Ego. - That is how the human as earthly being today is

constituted.

Physical organism: Physical body

Man regarded in a different way:

1. Solid organism Physical body

2. Fluid organism Etheric body

3. Aeriform organism Astral body

4. Warmth-organism Ego

Let us think, for example, of the blood. Inasmuch as it is mainly fluid,

inasmuch as this blood belongs to the fluid organism, we find in the blood

the etheric body which permeates it with its forces. But in the blood there

is also present what is generally called the warmth condition. But that

'organism' is by no means identical with the organism of the fluid blood as

such. If we were to investigate this - and it can also be done with physical

methods of investigation - we should find in registering the warmth in the

different parts of the human organism that the warmth cannot be identified

with the fluid organism or with any other.

Directly we reflect about man in this way we find that it is impossible for

our thought to come to a standstill within the limits of the human organism

itself. We can remain within these limits only if we are thinking merely of

the solid organism which is shut off by the skin from what is outside it.

Even this, however, is only apparently so. The solid structure is generally

regarded as if it were a firm, self-enclosed block; but it is also inwardly

differentiated and is related in manifold ways to the solid earth as a

whole. This is obvious from the fact that the different solid substances

have, for example, different weights; this alone shows that the solids

within the human organism are differentiated, have different specific

weights in man. In regard to the physical organism, therefore, the human

being is related to the earth as a whole. Nevertheless it is possible,

according at least to external evidence, to place spatial limits around the

physical organism.

It is different when we come to the second, the fluid organism that is

permeated by the etheric body. This fluid organism cannot be strictly

demarcated from the environment. Whatever is fluid in any area of space

adjoins the fluidic element in the environment. Although the fluid element

as such is present in the world outside us in a rarefied state, we cannot

make such a definite demarcation between the fluid element within man andr

the fluid element outside man, as in the case of the solid organism. The

boundary between man's inner fluid organism and the fluid element in the

external world must therefore be left indefinite.

This is even more emphatically the case when we come to consider the

aeriform organism which is permeated by the forces of the astral body. The

air within us at a certain moment was outside us a moment before, and it

will soon be outside again. We are drawing in and giving out the aeriform

element all the time. We can really think of the air as such which surrounds

our earth, and say: it penetrates into our organism and withdraws again; but

by penetrating into our organism it becomes an integral part of us. In our

aeriform organism we actually have something that constantly builds itself

up out of the whole atmosphere and then withdraws again into the atmosphere.

Whenever we breathe in, something is built up within us, or, at the very

least, each indrawn breath causes a change, a modification, in an upbuilding

process within us. Similarly, a destructive, partially destructive, process

takes place whenever we breathe out. Our aeriform organism undergoes a

certain change with every indrawn breath; it is not exactly newly born, but

it undergoes a change, both when we breathe in and when we breathe out. When

we breathe out, the aeriform organism does not, of course, die, it merely

undergoes a change; but there is constant interaction between the aeriform

organism within us and the air outside. The usual trivial conceptions of the

human organism can only be due to the failure to realize that there is but a

slight degree of difference between the aeriform organism and the solid

organism. And now we come to the warmth-organism. It is of course quite in

keeping with materialistic-mechanistic thought to study only the solid

organism and to ignore the fluid organism, the aeriform organism, and the

warmth-organism. But no real knowledge of man's being can be acquired unless

we are willing to acknowledge this membering into a warmth-organism, an

aeriform organism, a fluid organism, and an earth organism (solid).

The warmth-organism is paramountly the field of the Ego. The Ego itself is

that spirit-organization which imbues with its own forces the warmth that is

within us, and governs and gives it configuration, not only externally but

also inwardly. We cannot understand the life and activity of the soul unless

we remember that the Ego works directly upon the warmth. It is primarily the

Ego in man which activates the will, generates impulses of will. Ñ How does

the Ego generate impulses of will? From a different point of view we have

spoken of how impulses of will are connected with the earthly sphere, in

contrast to the impulses of thought and ideation which are connected with

forces outside and beyond the earthly sphere. But how does the Ego, which

holds together the impulses of will, send these impulses into the organism,

into the whole being of man? This is achieved through the fact that the will

works primarily in the warmth-organism. An impulse of will proceeding from

the Ego works upon the warmth-organism. Under present earthly conditions it

is not possible for what I shall now describe to you to be there as a

concrete reality. Nevertheless it can be envisaged as something that is

essentially present in man. It can be envisaged if we disregard the physical

organization within the space bounded by the human skin. We disregard this,

also the fluid organism, and the aeriform organism. The space then remains

filled with nothing but warmth which is, of course, in communication with

the warmth outside. But what is active in this warmth, what sets it in flow,

stirs it into movement, makes it into an organism Ñ is the Ego.

The astral body of man contains within it the forces of feeling. The astral

body brings these forces of feeling into physical operation in man's

aeriform organism.

As an earthly being, man's constitution is such that, by way of the

warmth-organism, his Ego gives rise to what comes to expression when he acts

in the world as a being of will. The feelings experienced in the astral body

and coming to expression in the earthly organization manifest in the

aeriform organism. And when we come to the etheric organism, to the etheric

body, we find within it the conceptual process, in so far as this has a

pictorial character Ñ more strongly pictorial than we are consciously aware

of to begin with, for the physical body still intrudes and tones down the

pictures into mental concepts. This process works upon the fluid organism.

This shows us that by taking these different organisms in man into account

we come nearer to the life of soul. Materialistic observation, which stops

short at the solid structure and insists that in the very nature of things

water cannot become an organism, is bound to confront the life of soul with

complete lack of understanding; for it is precisely in these other organisms

that the life of soul comes to immediate expression. The solid organism

itself is, in reality, only that which provides support for the other

organisms. The solid organism stands there as a supporting structure

composed of bones, muscles, and so forth. Into this supporting structure is

membered the fluid organism with its own inner differentiation and

configuration; in this fluid organism vibrates the etheric body, and within

this fluid organism the thoughts are produced. How are the thoughts

produced? Through the fact that within the fluid organism something asserts

itself in a particular metamorphosis Ñ namely, what we know in the external

world as tone.

Tone is, in reality, something that leads the ordinary mode of observation

very much astray. As earthly human beings we perceive the tone as being

borne to us by the air. But in point of fact the air is only the transmitter

of the tone, which actually weaves in the air. And anyone who assumes that

the tone in its essence is merely a matter of air-vibrations is like a

person who says: Man has only his physical organism, and there is no soul in

it. If the air-vibrations are thought to constitute the essence of the tone,

whereas they are in truth merely its external expression, this is the same

as seeing only the physical organism with no soul in it. The tone which

lives in the air is essentially an etheric reality. And the tone we hear by

way of the air arises through the fact that the air is permeated by the Tone

Ether (see Diagram III) which is the same as the Chemical Ether. In

permeating the air, this Chemical Ether imparts what lives within it to the

air, and we become aware of what we call the tone.

In addition to the solid man, therefore, we must bear in mind the 'fluid

man' and also the 'aeriform man.' For the air that is within us, in regard

to its organization and its differentiations, is an organism in the same

sense as the solid organism, only it is gaseous, aeriform, and in motion.

And finally, the warmth in us is not a uniform warmth extending over the

whole human being, but is also delicately organized. As soon, however, as we

begin to speak of the fluid organism which fills the same space that is

occupied by the solid organism, we realize immediately that we cannot speak

of this fluid organism in earthly man without speaking of the etheric body

which permeates this fluid organism and fills it with forces. The physical

organism exists for itself, as it were; it is the physical body; in so far

as we consider it in its entirety, we regard it, to begin with, as a solid

organism. This is the physical body.

We then come to consider the fluid organism, which cannot, of course, be

investigated in the same way as the solid organism, by dissection, but which

must be conceived as an inwardly mobile, fluidic organism. It cannot be

studied unless we think of it as permeated by the etheric body. Thirdly,

there is the aeriform organism which again cannot be studied unless we think

of it as permeated with forces by the astral body. Fourthly, there is the

warmth-organism with all its inner differentiation. It is permeated by the

forces of the Ego. - That is how the human as earthly being today is

constituted.

Physical organism: Physical body

Man regarded in a different way:

1. Solid organism Physical body

2. Fluid organism Etheric body

3. Aeriform organism Astral body

4. Warmth-organism Ego

Let us think, for example, of the blood. Inasmuch as it is mainly fluid,

inasmuch as this blood belongs to the fluid organism, we find in the blood

the etheric body which permeates it with its forces. But in the blood there

is also present what is generally called the warmth condition. But that

'organism' is by no means identical with the organism of the fluid blood as

such. If we were to investigate this - and it can also be done with physical

methods of investigation - we should find in registering the warmth in the

different parts of the human organism that the warmth cannot be identified

with the fluid organism or with any other.

Directly we reflect about man in this way we find that it is impossible for

our thought to come to a standstill within the limits of the human organism

itself. We can remain within these limits only if we are thinking merely of

the solid organism which is shut off by the skin from what is outside it.

Even this, however, is only apparently so. The solid structure is generally

regarded as if it were a firm, self-enclosed block; but it is also inwardly

differentiated and is related in manifold ways to the solid earth as a

whole. This is obvious from the fact that the different solid substances

have, for example, different weights; this alone shows that the solids

within the human organism are differentiated, have different specific

weights in man. In regard to the physical organism, therefore, the human

being is related to the earth as a whole. Nevertheless it is possible,

according at least to external evidence, to place spatial limits around the

physical organism.

It is different when we come to the second, the fluid organism that is

permeated by the etheric body. This fluid organism cannot be strictly

demarcated from the environment. Whatever is fluid in any area of space

adjoins the fluidic element in the environment. Although the fluid element

as such is present in the world outside us in a rarefied state, we cannot

make such a definite demarcation between the fluid element within man andr

the fluid element outside man, as in the case of the solid organism. The

boundary between man's inner fluid organism and the fluid element in the

external world must therefore be left indefinite.

This is even more emphatically the case when we come to consider the

aeriform organism which is permeated by the forces of the astral body. The

air within us at a certain moment was outside us a moment before, and it

will soon be outside again. We are drawing in and giving out the aeriform

element all the time. We can really think of the air as such which surrounds

our earth, and say: it penetrates into our organism and withdraws again; but

by penetrating into our organism it becomes an integral part of us. In our

aeriform organism we actually have something that constantly builds itself

up out of the whole atmosphere and then withdraws again into the atmosphere.

Whenever we breathe in, something is built up within us, or, at the very

least, each indrawn breath causes a change, a modification, in an upbuilding

process within us. Similarly, a destructive, partially destructive, process

takes place whenever we breathe out. Our aeriform organism undergoes a

certain change with every indrawn breath; it is not exactly newly born, but

it undergoes a change, both when we breathe in and when we breathe out. When

we breathe out, the aeriform organism does not, of course, die, it merely

undergoes a change; but there is constant interaction between the aeriform

organism within us and the air outside. The usual trivial conceptions of the

human organism can only be due to the failure to realize that there is but a

slight degree of difference between the aeriform organism and the solid

organism. And now we come to the warmth-organism. It is of course quite in

keeping with materialistic-mechanistic thought to study only the solid

organism and to ignore the fluid organism, the aeriform organism, and the

warmth-organism. But no real knowledge of man's being can be acquired unless

we are willing to acknowledge this membering into a warmth-organism, an

aeriform organism, a fluid organism, and an earth organism (solid).

The warmth-organism is paramountly the field of the Ego. The Ego itself is

that spirit-organization which imbues with its own forces the warmth that is

within us, and governs and gives it configuration, not only externally but

also inwardly. We cannot understand the life and activity of the soul unless

we remember that the Ego works directly upon the warmth. It is primarily the

Ego in man which activates the will, generates impulses of will. Ñ How does

the Ego generate impulses of will? From a different point of view we have

spoken of how impulses of will are connected with the earthly sphere, in

contrast to the impulses of thought and ideation which are connected with

forces outside and beyond the earthly sphere. But how does the Ego, which

holds together the impulses of will, send these impulses into the organism,

into the whole being of man? This is achieved through the fact that the will

works primarily in the warmth-organism. An impulse of will proceeding from

the Ego works upon the warmth-organism. Under present earthly conditions it

is not possible for what I shall now describe to you to be there as a

concrete reality. Nevertheless it can be envisaged as something that is

essentially present in man. It can be envisaged if we disregard the physical

organization within the space bounded by the human skin. We disregard this,

also the fluid organism, and the aeriform organism. The space then remains

filled with nothing but warmth which is, of course, in communication with

the warmth outside. But what is active in this warmth, what sets it in flow,

stirs it into movement, makes it into an organism Ñ is the Ego.

The astral body of man contains within it the forces of feeling. The astral

body brings these forces of feeling into physical operation in man's

aeriform organism.

As an earthly being, man's constitution is such that, by way of the

warmth-organism, his Ego gives rise to what comes to expression when he acts

in the world as a being of will. The feelings experienced in the astral body

and coming to expression in the earthly organization manifest in the

aeriform organism. And when we come to the etheric organism, to the etheric

body, we find within it the conceptual process, in so far as this has a

pictorial character Ñ more strongly pictorial than we are consciously aware

of to begin with, for the physical body still intrudes and tones down the

pictures into mental concepts. This process works upon the fluid organism.

This shows us that by taking these different organisms in man into account

we come nearer to the life of soul. Materialistic observation, which stops

short at the solid structure and insists that in the very nature of things

water cannot become an organism, is bound to confront the life of soul with

complete lack of understanding; for it is precisely in these other organisms

that the life of soul comes to immediate expression. The solid organism

itself is, in reality, only that which provides support for the other

organisms. The solid organism stands there as a supporting structure

composed of bones, muscles, and so forth. Into this supporting structure is

membered the fluid organism with its own inner differentiation and

configuration; in this fluid organism vibrates the etheric body, and within

this fluid organism the thoughts are produced. How are the thoughts

produced? Through the fact that within the fluid organism something asserts

itself in a particular metamorphosis Ñ namely, what we know in the external

world as tone.

Tone is, in reality, something that leads the ordinary mode of observation

very much astray. As earthly human beings we perceive the tone as being

borne to us by the air. But in point of fact the air is only the transmitter

of the tone, which actually weaves in the air. And anyone who assumes that

the tone in its essence is merely a matter of air-vibrations is like a

person who says: Man has only his physical organism, and there is no soul in

it. If the air-vibrations are thought to constitute the essence of the tone,

whereas they are in truth merely its external expression, this is the same

as seeing only the physical organism with no soul in it. The tone which

lives in the air is essentially an etheric reality. And the tone we hear by

way of the air arises through the fact that the air is permeated by the Tone

Ether (see Diagram III) which is the same as the Chemical Ether. In

permeating the air, this Chemical Ether imparts what lives within it to the

air, and we become aware of what we call the tone.

This Tone Ether or Chemical Ether is essentially active in our fluid

organism. We can therefore make the following distinction: In our fluid

organism lives our own etheric body; but in addition there penetrates into

it (the fluid organism) from every direction the Tone Ether which underlies

the tone. Please distinguish carefully here. We have within us our etheric

body; it works and is active by giving rise to thoughts in our fluid

organism. But what may be called the Chemical Ether continually streams in

and out of our fluid organism. Thus we have an etheric organism complete in

itself, consisting of Chemical Ether, Warmth-Ether, Light-Ether, Life-Ether,

and in addition we find in it, in a very special sense, the Chemical Ether

which streams in and out by way of the fluid organism.

(Lecture 1-portion, December 17, 1920)

--

Think of a person whose soul is fired with enthusiasm for a high moral

ideal, for the ideal of generosity, of freedom, of goodness, of love, or

whatever it may be. He may also feel enthusiasm for examples of the

practical expression of these ideals. But nobody can conceive that the

enthusiasm which fires the soul penetrates into the bones and muscles as

described by modern physiology or anatomy. If you really take counsel with

yourself, however, you will find it quite possible to conceive that when one

has enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, this enthusiasm has an effect upon

the warmth organism. Ñ There, you see, we have come from the realm of soul

into the physical!

Taking this as an example, we may say: Moral ideals come to expression in an

enhancement of warmth in the warmth-organism. Not only is man warmed in soul

through what he experiences in the way of moral ideals, but he becomes

organically warmer as well Ñ though this is not so easy to prove with

physical instruments. Moral ideals, then, have a stimulating, invigorating

effect upon the warmth-organism.

(Lecture 2-portion, December 18, 1920)

--

Reference:

Rudolf Steiner

*The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man*

Three Lectures given in Dornach, Switzerland, December 17th - 20th, 1920, GA 202.

This Tone Ether or Chemical Ether is essentially active in our fluid

organism. We can therefore make the following distinction: In our fluid

organism lives our own etheric body; but in addition there penetrates into

it (the fluid organism) from every direction the Tone Ether which underlies

the tone. Please distinguish carefully here. We have within us our etheric

body; it works and is active by giving rise to thoughts in our fluid

organism. But what may be called the Chemical Ether continually streams in

and out of our fluid organism. Thus we have an etheric organism complete in

itself, consisting of Chemical Ether, Warmth-Ether, Light-Ether, Life-Ether,

and in addition we find in it, in a very special sense, the Chemical Ether

which streams in and out by way of the fluid organism.

(Lecture 1-portion, December 17, 1920)

--

Think of a person whose soul is fired with enthusiasm for a high moral

ideal, for the ideal of generosity, of freedom, of goodness, of love, or

whatever it may be. He may also feel enthusiasm for examples of the

practical expression of these ideals. But nobody can conceive that the

enthusiasm which fires the soul penetrates into the bones and muscles as

described by modern physiology or anatomy. If you really take counsel with

yourself, however, you will find it quite possible to conceive that when one

has enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, this enthusiasm has an effect upon

the warmth organism. Ñ There, you see, we have come from the realm of soul

into the physical!

Taking this as an example, we may say: Moral ideals come to expression in an

enhancement of warmth in the warmth-organism. Not only is man warmed in soul

through what he experiences in the way of moral ideals, but he becomes

organically warmer as well Ñ though this is not so easy to prove with

physical instruments. Moral ideals, then, have a stimulating, invigorating

effect upon the warmth-organism.

(Lecture 2-portion, December 18, 1920)

--

Reference:

Rudolf Steiner

*The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man*

Three Lectures given in Dornach, Switzerland, December 17th - 20th, 1920, GA 202.

BACK TO STORM'S JOURNAL

submit an article.

eMail to: johnrpenner@earthlink.net

this page last updated: February 15, 2001

this page last updated: February 15, 2001

--| The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality --| and the Physical Constitution of Man http://www.elib.com/Steiner/Lectures/BridgeBet/ When man is studied by modern scientific thinking, one part only of the being is taken into consideration. No account whatever is taken of the fact that in addition to his physical body, man also has higher members. But we will leave this aside today and think about something that is more or less recognized in science and has also made its way into the general consciousness. In studying the human being, only those elements which can be pictured as solid, or solid-fluidic, are regarded as belonging to his organism. It is, of course, acknowledged that the fluid and the aeriform elements pass into and out of the human being, but these are not in themselves considered to be integral members of the human organism. The warmth within man which is greater than that of his environment is regarded as a state or condition of his organism, but not as an actual member of his constitution. We shall presently see what I mean by saying this. I have already drawn attention to the fact that when we study the rising and falling of the cerebral fluid through the spinal canal, we can observe a regular up-and-down oscillatory movement caused by inhalation and exhalation; when we breathe in, the cerebral fluid is driven upwards and strikes, as it were, against the brain-structure; when we breathe out, the fluid sinks again. These processes in the purely liquid components of the human organism are not considered to be part and parcel of the organism itself. The general idea is that man, as a physical structure, consists of the more or less solid, or at most solid-fluid, substances found in him.

Man is pictured as a structure built up from these more or less solid substances (see Diagram I). The other elements, the fluid element, as I have shown by the example of the cerebral fluid, and the aeriform element, are not regarded by anatomy and physiology as belonging to the human organism as such. It is said: Yes, the human being draws in the air which follows certain paths in his body and also has certain definite functions. This air is breathed out again. - Then people speak of the warmth condition of the body, but in reality they regard the solid element as the only organizing factor and do not realize that in addition to this solid structure they should also see the whole man as a column of fluid (Diagram II, blue), as being permeated with air (red) and as a being in whom there is a definite degree of warmth (yellow). More exact study shows that just as the solid or solid-fluid constituents are to be considered as an integral part or member of the organism, so the actual fluidity should not be thought of as so much uniform fluid, but as being differentiated and organized - though the process here is a more fluctuating one - and having its own particular significance.

In addition to the solid man, therefore, we must bear in mind the 'fluid man' and also the 'aeriform man.' For the air that is within us, in regard to its organization and its differentiations, is an organism in the same sense as the solid organism, only it is gaseous, aeriform, and in motion. And finally, the warmth in us is not a uniform warmth extending over the whole human being, but is also delicately organized. As soon, however, as we begin to speak of the fluid organism which fills the same space that is occupied by the solid organism, we realize immediately that we cannot speak of this fluid organism in earthly man without speaking of the etheric body which permeates this fluid organism and fills it with forces. The physical organism exists for itself, as it were; it is the physical body; in so far as we consider it in its entirety, we regard it, to begin with, as a solid organism. This is the physical body. We then come to consider the fluid organism, which cannot, of course, be investigated in the same way as the solid organism, by dissection, but which must be conceived as an inwardly mobile, fluidic organism. It cannot be studied unless we think of it as permeated by the etheric body. Thirdly, there is the aeriform organism which again cannot be studied unless we think of it as permeated with forces by the astral body. Fourthly, there is the warmth-organism with all its inner differentiation. It is permeated by the forces of the Ego. - That is how the human as earthly being today is constituted. Physical organism: Physical body Man regarded in a different way: 1. Solid organism Physical body 2. Fluid organism Etheric body 3. Aeriform organism Astral body 4. Warmth-organism Ego Let us think, for example, of the blood. Inasmuch as it is mainly fluid, inasmuch as this blood belongs to the fluid organism, we find in the blood the etheric body which permeates it with its forces. But in the blood there is also present what is generally called the warmth condition. But that 'organism' is by no means identical with the organism of the fluid blood as such. If we were to investigate this - and it can also be done with physical methods of investigation - we should find in registering the warmth in the different parts of the human organism that the warmth cannot be identified with the fluid organism or with any other. Directly we reflect about man in this way we find that it is impossible for our thought to come to a standstill within the limits of the human organism itself. We can remain within these limits only if we are thinking merely of the solid organism which is shut off by the skin from what is outside it. Even this, however, is only apparently so. The solid structure is generally regarded as if it were a firm, self-enclosed block; but it is also inwardly differentiated and is related in manifold ways to the solid earth as a whole. This is obvious from the fact that the different solid substances have, for example, different weights; this alone shows that the solids within the human organism are differentiated, have different specific weights in man. In regard to the physical organism, therefore, the human being is related to the earth as a whole. Nevertheless it is possible, according at least to external evidence, to place spatial limits around the physical organism. It is different when we come to the second, the fluid organism that is permeated by the etheric body. This fluid organism cannot be strictly demarcated from the environment. Whatever is fluid in any area of space adjoins the fluidic element in the environment. Although the fluid element as such is present in the world outside us in a rarefied state, we cannot make such a definite demarcation between the fluid element within man andr the fluid element outside man, as in the case of the solid organism. The boundary between man's inner fluid organism and the fluid element in the external world must therefore be left indefinite. This is even more emphatically the case when we come to consider the aeriform organism which is permeated by the forces of the astral body. The air within us at a certain moment was outside us a moment before, and it will soon be outside again. We are drawing in and giving out the aeriform element all the time. We can really think of the air as such which surrounds our earth, and say: it penetrates into our organism and withdraws again; but by penetrating into our organism it becomes an integral part of us. In our aeriform organism we actually have something that constantly builds itself up out of the whole atmosphere and then withdraws again into the atmosphere. Whenever we breathe in, something is built up within us, or, at the very least, each indrawn breath causes a change, a modification, in an upbuilding process within us. Similarly, a destructive, partially destructive, process takes place whenever we breathe out. Our aeriform organism undergoes a certain change with every indrawn breath; it is not exactly newly born, but it undergoes a change, both when we breathe in and when we breathe out. When we breathe out, the aeriform organism does not, of course, die, it merely undergoes a change; but there is constant interaction between the aeriform organism within us and the air outside. The usual trivial conceptions of the human organism can only be due to the failure to realize that there is but a slight degree of difference between the aeriform organism and the solid organism. And now we come to the warmth-organism. It is of course quite in keeping with materialistic-mechanistic thought to study only the solid organism and to ignore the fluid organism, the aeriform organism, and the warmth-organism. But no real knowledge of man's being can be acquired unless we are willing to acknowledge this membering into a warmth-organism, an aeriform organism, a fluid organism, and an earth organism (solid). The warmth-organism is paramountly the field of the Ego. The Ego itself is that spirit-organization which imbues with its own forces the warmth that is within us, and governs and gives it configuration, not only externally but also inwardly. We cannot understand the life and activity of the soul unless we remember that the Ego works directly upon the warmth. It is primarily the Ego in man which activates the will, generates impulses of will. Ñ How does the Ego generate impulses of will? From a different point of view we have spoken of how impulses of will are connected with the earthly sphere, in contrast to the impulses of thought and ideation which are connected with forces outside and beyond the earthly sphere. But how does the Ego, which holds together the impulses of will, send these impulses into the organism, into the whole being of man? This is achieved through the fact that the will works primarily in the warmth-organism. An impulse of will proceeding from the Ego works upon the warmth-organism. Under present earthly conditions it is not possible for what I shall now describe to you to be there as a concrete reality. Nevertheless it can be envisaged as something that is essentially present in man. It can be envisaged if we disregard the physical organization within the space bounded by the human skin. We disregard this, also the fluid organism, and the aeriform organism. The space then remains filled with nothing but warmth which is, of course, in communication with the warmth outside. But what is active in this warmth, what sets it in flow, stirs it into movement, makes it into an organism Ñ is the Ego. The astral body of man contains within it the forces of feeling. The astral body brings these forces of feeling into physical operation in man's aeriform organism. As an earthly being, man's constitution is such that, by way of the warmth-organism, his Ego gives rise to what comes to expression when he acts in the world as a being of will. The feelings experienced in the astral body and coming to expression in the earthly organization manifest in the aeriform organism. And when we come to the etheric organism, to the etheric body, we find within it the conceptual process, in so far as this has a pictorial character Ñ more strongly pictorial than we are consciously aware of to begin with, for the physical body still intrudes and tones down the pictures into mental concepts. This process works upon the fluid organism. This shows us that by taking these different organisms in man into account we come nearer to the life of soul. Materialistic observation, which stops short at the solid structure and insists that in the very nature of things water cannot become an organism, is bound to confront the life of soul with complete lack of understanding; for it is precisely in these other organisms that the life of soul comes to immediate expression. The solid organism itself is, in reality, only that which provides support for the other organisms. The solid organism stands there as a supporting structure composed of bones, muscles, and so forth. Into this supporting structure is membered the fluid organism with its own inner differentiation and configuration; in this fluid organism vibrates the etheric body, and within this fluid organism the thoughts are produced. How are the thoughts produced? Through the fact that within the fluid organism something asserts itself in a particular metamorphosis Ñ namely, what we know in the external world as tone. Tone is, in reality, something that leads the ordinary mode of observation very much astray. As earthly human beings we perceive the tone as being borne to us by the air. But in point of fact the air is only the transmitter of the tone, which actually weaves in the air. And anyone who assumes that the tone in its essence is merely a matter of air-vibrations is like a person who says: Man has only his physical organism, and there is no soul in it. If the air-vibrations are thought to constitute the essence of the tone, whereas they are in truth merely its external expression, this is the same as seeing only the physical organism with no soul in it. The tone which lives in the air is essentially an etheric reality. And the tone we hear by way of the air arises through the fact that the air is permeated by the Tone Ether (see Diagram III) which is the same as the Chemical Ether. In permeating the air, this Chemical Ether imparts what lives within it to the air, and we become aware of what we call the tone.

This Tone Ether or Chemical Ether is essentially active in our fluid organism. We can therefore make the following distinction: In our fluid organism lives our own etheric body; but in addition there penetrates into it (the fluid organism) from every direction the Tone Ether which underlies the tone. Please distinguish carefully here. We have within us our etheric body; it works and is active by giving rise to thoughts in our fluid organism. But what may be called the Chemical Ether continually streams in and out of our fluid organism. Thus we have an etheric organism complete in itself, consisting of Chemical Ether, Warmth-Ether, Light-Ether, Life-Ether, and in addition we find in it, in a very special sense, the Chemical Ether which streams in and out by way of the fluid organism. (Lecture 1-portion, December 17, 1920) -- Think of a person whose soul is fired with enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, for the ideal of generosity, of freedom, of goodness, of love, or whatever it may be. He may also feel enthusiasm for examples of the practical expression of these ideals. But nobody can conceive that the enthusiasm which fires the soul penetrates into the bones and muscles as described by modern physiology or anatomy. If you really take counsel with yourself, however, you will find it quite possible to conceive that when one has enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, this enthusiasm has an effect upon the warmth organism. Ñ There, you see, we have come from the realm of soul into the physical! Taking this as an example, we may say: Moral ideals come to expression in an enhancement of warmth in the warmth-organism. Not only is man warmed in soul through what he experiences in the way of moral ideals, but he becomes organically warmer as well Ñ though this is not so easy to prove with physical instruments. Moral ideals, then, have a stimulating, invigorating effect upon the warmth-organism. (Lecture 2-portion, December 18, 1920) -- Reference: Rudolf Steiner *The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man* Three Lectures given in Dornach, Switzerland, December 17th - 20th, 1920, GA 202.