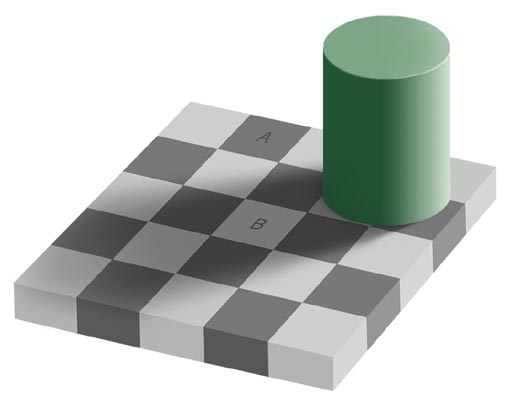

Image Rendered by: Edward Adelson

Although they look different, any Pixel Analyzer will show that

the stimuli of the squares marked 'A' and 'B' are EXACTLY the same -- Try it!

So if the colour doesn't lie in the stimulous, then where!?!?

One possibility -- advocated by noble-prize winning neurophysoligist

John Eccles -- is that Colours, such as Red, only exist for the MIND!

As Feigenbaum understood them, Goethe's ideas had true science in them.

They were hard and empirical. Over and over again, Goethe emphasized the

repeatability of his experiments. It was the perception of colour, to Goethe,

that was universal and objective. What scientific evidence was there for a

definable real-world quality of redness independent of our perception?

(James Gleick, 'Chaos', William Heinemann, London, 1988, pp. 165-7)

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer

in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is

taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be

a total mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is

bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the

wrod as a wlohe. Amzanig eh?

--

The niave realist looks for the causes within the phenomenon.

However from the monistic position, we might entertain the following

postulate: Humans recognize words because the Meaning / Content

doesn't exist merely in what you SEE; rather, their unity is first given

in conceptual form to our cognition.

Image Rendered by: Edward Adelson

Although they look different, any Pixel Analyzer will show that

the stimuli of the squares marked 'A' and 'B' are EXACTLY the same -- Try it!

So if the colour doesn't lie in the stimulous, then where!?!?

One possibility -- advocated by noble-prize winning neurophysoligist

John Eccles -- is that Colours, such as Red, only exist for the MIND!

As Feigenbaum understood them, Goethe's ideas had true science in them.

They were hard and empirical. Over and over again, Goethe emphasized the

repeatability of his experiments. It was the perception of colour, to Goethe,

that was universal and objective. What scientific evidence was there for a

definable real-world quality of redness independent of our perception?

(James Gleick, 'Chaos', William Heinemann, London, 1988, pp. 165-7)

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer

in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is

taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be

a total mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is

bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the

wrod as a wlohe. Amzanig eh?

--

The niave realist looks for the causes within the phenomenon.

However from the monistic position, we might entertain the following

postulate: Humans recognize words because the Meaning / Content

doesn't exist merely in what you SEE; rather, their unity is first given

in conceptual form to our cognition.

Thought as a Perceptual Instrument for Ideas

Does thinking even have any content if you disregard all visible reality,

if you disregard the sense-perceptible world of phenomena? Does there not

remain a total void, a pure phantasm, if we think away all

sense-perceptible content?

That this is indeed the case could very well be a widespread opinion, so

we must look at it a little more closely. As we have already noted above,

many people think of the entire system of concepts as in fact only a

photograph of the outer world. They do indeed hold onto the fact that our

knowing develops in theform of thinking, but demand nevertheless that a

'strictly objective science' take its content only from outside. According

to them the outer world must provide the substance that flows into our

concepts. Without the outer world, they maintain, these concepts are only

empty schemata without any content. If this outer world fell away,

concepts and ideas would no longer have any meaning, for they are there

for the sake of the outer world. One could call this view the negation of

the concept. For then the concept no longer has any significance at all

for the objective world. It is something added onto the latter. The world

would stand there in all its completeness even if there were no concepts.

For they in fact bring nothing new to the world. They contain nothing that

would not be there without them. They are there only because the knowing

subject wants to make use of them in order to have, in a form appropriate

to this subject, that which is otherwise already there. For this subject,

they are only mediators of a content that is of a non-conceptual nature.

This is the view presented.

If it were justified, one of the following three presuppositions would

have to be correct.

1. The world of concepts stands in a relationship to the outer world such

that it only reproduces the entire content of this world in a different

form. Here 'outer world' means the sense world. If that were the case, one

truly could not see why it would be necessary to lift oneself above the

sense world at all. The entire whys and wherefores of knowing would after

all already be given along with the sense world.

2. The world of concepts takes up, as its content, only a part of 'what

manifests to the senses.' Picture the matter so~nething like this. We make

a series of observations. We meet there with the most varied objects. In

doing so we notice that certain characteristics we discover in an object

have already been observed by us berore. Our eye scans a series of objects

A, B, C, D, etc. A has the characteristics p, q, a, r; B: l, m, h, n;

C: k, h, c, g; and D: p, u, a, v. In D we again meet the characteristics

a and p, which we have already encountered in A. We designate these

characteristics as essential. And insofar as A and D have the same

essential characteristics, we say that they are of the same kind. Thus we

bring A and D together by holding fast to their essential characteristics

in thinking. There we have a thinking that does not entirely coincide with

the sense world, a thinking that therefore cannot be accused of being

superfluous as in the case of the first presupposition above; nevertheless

it it still just as far from bringing anything new to the sense world. But

one can certainly raise the objection to this that, in order to recognize

which characteristics of a thing are essential, there must already be a

certain norm making it possible to distinguish the essential from the

inessential. This norm cannot lie in the object, for the object in fact

contains both what is essential and inessential in undivided unity.

Therefore this norm must after all be thinking's very own content.

This objection, however, does not yet entirely overturn this view. One can

say, namely, that it is an unjustified assumption to declare that this or

that is more essential or less essential for a thing. We are also not

concerned about this. It is merely a matter of our encountering certain

characteristics that are the same in several things and of our then

stating that these things are of the same kind. It is not at all a

question of whether these characteristics, which are the same, are also

essential. But this view presupposes something that absolutely does not

fit the facts. Two things of the same kind really have nothing at all in

common if a person remains only with sense experience. An example will

make this clear. The simplest example is the best, because it is the most

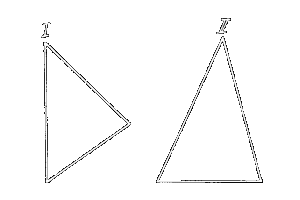

surveyable. Let us look at the following two triangles.

What is really the same about them if we remain with sense experience?

Nothing at all. What they have in common—namely, the law by which they are

formed and which brings it about that both fall under the concept

'triangle'— we can gain onlywhen we go beyond sense experience. The

concept 'triangle' comprises all triangles. We do not arrive at it merely

by looking at all the individual triangles. This concept always remains

the same for me no matter how often I might picture it, whereas I will

hardly ever view the same 'triangle' twice. What makes an individual

triangle into 'this' particular one and no other has nothing whatsoever to

do with the concept. A particular triangle is this particular one not

through the fact that it corresponds to that concept but rather because of

elements Iying entirely outside the concept: the length of its sides, size

of its angles, position, etc. But it is after all entirely inadmissible to

maintain that the content of the concept 'triangle' is drawn from the

objective sense world, when one sees that its content is not contained at

all in any sense-perceptible phenomenon.

3. Now there is yet a third possibility. The concept could in fact be the

mediator for grasping entities that are not sense-perceptible but that

still have a self-sustaining character. This latter would then be the

non-conceptual content of the conceptualforrn of our thinking. Anyone who

assumes such entities, existing beyond experience, and credits us with the

possibility of knowing about them must then also necessarily see the

concept as the interpreter of this knowing.

We will demonstrate the inadequacy of this view more specifically later.

Here we want only to note that it does not in any case speak against the

fact that the world of concepts has content. For, if the objects about

which one thinks lie beyond any experience and beyond thinking, then

thinking would all the more have to have within itself the content upon

which it finds its support. It could not, after all, think about objects

for which no trace is to be found within the world of thoughts.

It is in any case clear, therefore, that thinking is not an empty vessel;

rather, taken purely for itself, it is full of content; and its content

does not coincide with that of any other form of manifestation.

(Steiner, Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception,

Chapter 10, 1883)

What is really the same about them if we remain with sense experience?

Nothing at all. What they have in common—namely, the law by which they are

formed and which brings it about that both fall under the concept

'triangle'— we can gain onlywhen we go beyond sense experience. The

concept 'triangle' comprises all triangles. We do not arrive at it merely

by looking at all the individual triangles. This concept always remains

the same for me no matter how often I might picture it, whereas I will

hardly ever view the same 'triangle' twice. What makes an individual

triangle into 'this' particular one and no other has nothing whatsoever to

do with the concept. A particular triangle is this particular one not

through the fact that it corresponds to that concept but rather because of

elements Iying entirely outside the concept: the length of its sides, size

of its angles, position, etc. But it is after all entirely inadmissible to

maintain that the content of the concept 'triangle' is drawn from the

objective sense world, when one sees that its content is not contained at

all in any sense-perceptible phenomenon.

3. Now there is yet a third possibility. The concept could in fact be the

mediator for grasping entities that are not sense-perceptible but that

still have a self-sustaining character. This latter would then be the

non-conceptual content of the conceptualforrn of our thinking. Anyone who

assumes such entities, existing beyond experience, and credits us with the

possibility of knowing about them must then also necessarily see the

concept as the interpreter of this knowing.

We will demonstrate the inadequacy of this view more specifically later.

Here we want only to note that it does not in any case speak against the

fact that the world of concepts has content. For, if the objects about

which one thinks lie beyond any experience and beyond thinking, then

thinking would all the more have to have within itself the content upon

which it finds its support. It could not, after all, think about objects

for which no trace is to be found within the world of thoughts.

It is in any case clear, therefore, that thinking is not an empty vessel;

rather, taken purely for itself, it is full of content; and its content

does not coincide with that of any other form of manifestation.

(Steiner, Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception,

Chapter 10, 1883)

SUBMIT AN ARTICLE

posted: September 28, 2003

updated: march 21, 2007

|

Image Rendered by: Edward Adelson Although they look different, any Pixel Analyzer will show that the stimuli of the squares marked 'A' and 'B' are EXACTLY the same -- Try it! So if the colour doesn't lie in the stimulous, then where!?!? One possibility -- advocated by noble-prize winning neurophysoligist John Eccles -- is that Colours, such as Red, only exist for the MIND! As Feigenbaum understood them, Goethe's ideas had true science in them. They were hard and empirical. Over and over again, Goethe emphasized the repeatability of his experiments. It was the perception of colour, to Goethe, that was universal and objective. What scientific evidence was there for a definable real-world quality of redness independent of our perception? (James Gleick, 'Chaos', William Heinemann, London, 1988, pp. 165-7)

What is really the same about them if we remain with sense experience? Nothing at all. What they have in common—namely, the law by which they are formed and which brings it about that both fall under the concept 'triangle'— we can gain onlywhen we go beyond sense experience. The concept 'triangle' comprises all triangles. We do not arrive at it merely by looking at all the individual triangles. This concept always remains the same for me no matter how often I might picture it, whereas I will hardly ever view the same 'triangle' twice. What makes an individual triangle into 'this' particular one and no other has nothing whatsoever to do with the concept. A particular triangle is this particular one not through the fact that it corresponds to that concept but rather because of elements Iying entirely outside the concept: the length of its sides, size of its angles, position, etc. But it is after all entirely inadmissible to maintain that the content of the concept 'triangle' is drawn from the objective sense world, when one sees that its content is not contained at all in any sense-perceptible phenomenon. 3. Now there is yet a third possibility. The concept could in fact be the mediator for grasping entities that are not sense-perceptible but that still have a self-sustaining character. This latter would then be the non-conceptual content of the conceptualforrn of our thinking. Anyone who assumes such entities, existing beyond experience, and credits us with the possibility of knowing about them must then also necessarily see the concept as the interpreter of this knowing. We will demonstrate the inadequacy of this view more specifically later. Here we want only to note that it does not in any case speak against the fact that the world of concepts has content. For, if the objects about which one thinks lie beyond any experience and beyond thinking, then thinking would all the more have to have within itself the content upon which it finds its support. It could not, after all, think about objects for which no trace is to be found within the world of thoughts. It is in any case clear, therefore, that thinking is not an empty vessel; rather, taken purely for itself, it is full of content; and its content does not coincide with that of any other form of manifestation. (Steiner, Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception, Chapter 10, 1883)